- Home

- Projects / Performances / Creative Services

- Award-Winning Solo Percussion Concerts and Word-Beat

- Educational School Assembly / Family Programs

- Live Film Score Concerts

- "Global Standards" World/Jazz Ensemble

- Multi-Media Presentation Sounds You Can SEE

- Sound Installation

- Sound Design for Theatre / Film / TV

- Recording Session Services

- Healing Therapeutic Sound and Community Drumming

- Study with Tom

- Store

- Calendar

- Contact

- Blog

Visit Tom's artist page on LP Music

Read an interview with Tom and director Aaron Posner in dctheatrescene.com

Read Tom's review in Frederick News Post

Read Tom's interview with Willard Jenkins online publication "Openskyjazz.com"

Read Tom's interview with DC Metro Arts

Download clipping image

Print Ready Images

Download clipping image

Print Ready Images

Portraits: Tom Teasley

Not your average world-beat-spoken-word-bop-renovator, by T. Bruce Wittet for Modern Drummer Magazine

Rhythms and Rhymes of the Street

You thought you had it bad promoting your drumming.

Some day, just to build character, try to book an act consisting of a drummer and a poet. Doors close in your face. People raise an eyebrow. Yet Tom Teasley persists in his struggle and has met with success. He and actor / poet Charles Williams now have a busy concert schedule and perform in inner city Washington schools.

And that's only part of what Tom Teasley has going for him. You get a glimpse at the rest in his video The Drum: Ancient Traditions Today. At one moment he's doing a funky street beat on drums. Then he strikes the malletKAT to his right to get a dark, blossoming swell. Then it's over to a hand drum, or maybe to the roughly hammered Chinese cymbal above his hi-hat. Partly following a rough chart and partly following his instincts, he keeps you on your toes. Just when you think you've got him figured out, he pulls another rabbit out of his hat.

But don’t get the idea the Teasley is a dabbler. On the contrary, he spends time learning proper techniques and respecting the traditions of all his instruments, ethnic or otherwise. It's just that he glides around his kit, hand drums, and electronics, it looks simple and free.

Of course, that's what makes good art. Watching Tom Teasley can generate all sorts of ideas on how to make use of resources that stare us in the face. Take the snare drum, for example. He'll cross-stick it, turn the snares off and play it with his fingers like a piano, then grab sticks and do a funk beat. No instrument has a limitation for him. Once he learns the basic rules - like how to work a talking drum - he'll go off in his own direction. Give Tom a bass drum, a snare drum, and a djembé, and he'll give you part Stravinsky, part Art Blakey.

Teasley gets considerable help from drum manufacturers, academic institution, and kindred spirits. Chief among his collaborators is folk / operatic vocalist Charles Williams, fellow artist in residence at Washington's Levine School of Music. The two strike a vivid image. There's Tom in flowing white smock, his shaven head shining, and there's Charles, who could double for actor James Earl Jones.

"I have nothing up my sleeve!" thunders Williams at the outset of the duo's video Poetry Prose Percussion & Song, proclaiming righteous intentions. His partner, on the other hand, has a whole arsenal of surprises, including techniques of fingering, brushing, scraping, and sticking his drums, cymbals, and ethnic percussion.

Even if you didn't buy the poetry / drums thing initially, within a couple of minutes into their video you're hooked. It's the restraint they exercise, a control that arises from proper pacing and the knowledge of when to back off once they make a point.

Not that Tom lives by poetry alone. He has recently released a CD called Global Standard Time, in which he covers Monk and other standards. Check his versions of McCoy Tyner's "Passion Dance," featuring electric guitar and trombone. Here again, Tom demonstrates his ability to inject new life into familiar themes.

Looking back, Tom reflects that his current creative bonanza probably had little to do with his stint in the Navy band. In fact, he termed it a "creative Wasteland." But it gave him daily playing experience - and enabled him to buy a house. Before that, he toddled along like the rest of us, self-taught until he got serious and took lessons with Al Merz of The National Symphony. The next step was Baltimore's Peabody Conservatory.

"After I graduated," Tom recalls, "I went on the road with Catfish Hodge. We'd tour a lot to New Orleans. We played at Tipitina's with Professor Longhair. That was a huge influence. I'd hang with Johnny Vidacovich, and we'd talk about drums. I'd watch him play every night, and I fell into that sort of thing. It wasn't on purpose, though! I was trained as a classical percussionist."

How does a classical player learn how to groove so well? Tom smiles: "It's by design that it worked out the way. I studied with Joe Morello and with Glen Velez. I would take the conceptual thing from Glen and combine it with the technical exercises I got from Joe. Right now I'm working with ride patterns on shakers, going through Alan Dawson-type exercises with the Ted Reed book."

Tom has shakers shaped like shoe polish tins, which fit snugly in his palm. "They're made out of wood, and they're flat on top and bottom," he says. "That allows me to get different colors by turning them perpendicular to the floor, flat, or somewhere in between. And they're small enough that I can cover them with my hand to muffle them. When you're playing a drum or a cymbal, you're playing one surface. With a shaker, though, you're dealing with all the areas in between, and you're manipulating the flow of gravity."

Tom is similarly casual with his electronics. He'll use stock synth sounds if he has to. "I'm using a Yamaha QY700 sequencer. I'll do a lot of manipulation with its' internal sounds. I'm interested in what would happen if, say, I sampled a frame drum and a timpani playing the same pitch - but the timpani with a mallet and the frame drum with my hand - and blended them together. I like to think that the stuff I do on electronics is an organic progression from these ancient percussion practices - just using the equipment available today."

Ultimately, electronic palettes are a means, not an end, says Tom. "It's still all about what kind of gut, rhythmic hook it's got. If it doesn't have that, then it's lost what drew me to it in the first place."

That gut feeling is what drew Tom to Charles Williams, Tom recalls, "I had heard a tape of Max Roach playing along with the Martin Luther King 'I Have A Dream' speech. I thought that it was effective. But how much more effective would it have been if they were doing it in real time and reacting with the phrasing. For a concert, we did the Martin Luther King speech 'I Still Believe.' The audience was crying. It was really moving."

Teasley and Williams perform a piece called "The Creation," featuring the poetry of James Weldon Johnson and lots of percussion, both scripted and improvised. With only one drummer to handle all the parts, it could have easily gone vaudeville. "It could have ended up being a Spike Jones thing," agrees Tom. "People immediately assume it's the quasi-beatnik thing with the bongos, but it's much more compositional. I'm reading the text. Beside the text I'll write a certain figure or style."

It means Teasley has to edit on the run. He can't beat a particular sound to death, nor can he strike blindly at his collection of instruments. As they used to say, it's all about pacing. "That's largely an influence of classical music, "Tom advises. "I try to borrow from the way composers orchestrate colors and interesting sound combinations - a gong, a triangle, or maybe a cymbal played with a mallet."

On drumset, he will frequently play with bare hands. "A lot of the drumming on my video was influenced by conga or doumbek playing, where I'm trying to exploit the nuances of the drum by virtue of how much pressure my hand is putting on the head. I use the Senegalese technique of playing with one stick and one hand, making a lot of variance of the pressure on the drum-head."

A high, bop tuning will not work, according to Teasley. "I'll tune the top heads of the drums looser. As a result, the head has more play in it, so when I'm pressing with my hand it allows the pitch to bend. I'm using Remo Renaissance heads, and they sound really natural with the other percussion." The latter includes hand drums fashioned by former clay artist Steve Wright, who also produced two of Teasley's videos.

The Levine School has recently given Tom a grant. "It's to do concerts using my eclectic approach to percussion," he says. "I'm going to co-op them with Sabian and Yamaha. The school supplies a lot of concert opportunities." Tom has hired someone to market his CD, Global Standard Time, which he places in "crossover" territory between world music and jazz. He is aware of the criticism that states that by blending the various ethnic musics, we risk diluting them. "I hear that criticism, although not leveled at me. The only thing I say is that I try to be respectful of the traditions, and combine them in a way that ultimately brings out the best of everything."

Back to that shaven head and white shirt. Is it a sign of at least a shred of religious fervor? "It almost sounds trite when I say it, but to me, drumming is my religion - or a manifestation of it. Especially the stuff I do with Charles. We do concerts in the school system, and it's very spiritual, although you might not want to denote it as such. But drumming has been part of religious traditions since the beginning of time"

Check out Tom and his CD and video releases at www.tomteasley.com, email his distributor at northcountry@cadencebuilding.com or contact Wright Hand Drum Company at (800) 990-HAND.

World Percussion & Rhythm Interview

Volume VI Issue 2 2004

WPR: When did you first become interested in percussion and was your family supportive? Who were your first influences?

Teasley: I first became interested in percussion when I was about 12. I was lucky because in the neighborhood where I lived there were some older kids who played guitar and bass. I was the only kid around who could hold the sticks. I had only a snare drum and cymbal and played some gigs with only that equipment. I used the money from gigs and a paper route to add, piece by piece, a bass drum, tom-tom and hi-hat. It was actually a good way to add equipment because I really learned to explore the instruments I had before I added new ones. My first influences were Ringo and Charlie Watts and the Mo-Town and Stax recordings. By the time I was in 8th grade I had discovered the virtuoso rock drummers like Mitch Mitchell and Ginger Baker. I was also very much influenced by B.B. King, Muddy Waters and Albert King. Soon I discovered Miles Davis' "Bitches Brew" and there was no looking back. My grandmother was a professional musician and my parents were extremely supportive.

WPR: How did you teach yourself drum set? Tell us about your early experiences playing in rock bands and with various blues bands. What was life like in the band scene and "on the road?"

Teasley: I taught myself by playing along with recordings. My bands were playing at dances and being advertised on the radio by the time I was in 7th grade. We had a repertoire that included "Cold Sweat" by James Brown and "Fire" by Jimi Hendrix. So I learned some pretty complex material by ear. By the time I was 16 I had graduated to playing in the thriving strip club scene that was so prevalent in D.C. on 14th Street. It was at that time I knew I wanted music to be my life's work. (Laughs) When I arrived at Peabody Conservatory I was far behind the other students in classical percussion but I was soon gigging in Baltimore and Pennsylvania with an organ trio. I took a year off from school to tour, performing at hotels and resorts around the country. So I had a year straight on the road between 20 and 21 years of age. It was an invaluable experience, playing jazz, R & B and popular music. It is unfortunate there aren't opportunities like that for today's young musicians. I not only learned about performing different styles but also how to conduct myself as a professional. When I finally graduated while my fellow students were taking orchestra auditions, I was touring with "Catfish Hodge band." It was a national touring blues band that would open shows for Muddy Waters, Little Feat and Bonnie Raitt. We played often at "Tipitina's" in New Orleans trading sets with "Professor Longhair." Johnny Vidacovich was the drummer and I learned a lot just watching him and hanging after the shows.

WPR: Tell us about your formal studies and your important teachers. How did you manage to study so many different kinds of percussion instruments?

Teasley: My first teacher was Al Merz, a percussionist with the National Symphony Orchestra. He did a wonderful job teaching me to become a more literate musician. In two years he took a somewhat accomplished drum set "ear player" and prepared me for audition on orchestral snare drum, marimba and timpani to enter Peabody Conservatory. While at Peabody I studied percussion with Charles Memphis who was a Greek drummer and excellent drum set and mallet player. He was perhaps my first exposure to world percussion. He wrote many snare drum and percussion pieces that used Middle Eastern rhythms. I studied timpani with Fred Begun who was principal timpanist with the National Symphony for 49 years. Even though I never became a great timpanist his concepts of tone production and musical passion are still with me. After I graduated I began studies with Joe Morello for several years. His technical and rhythmic mastery is the basis for much of my work today. Joe's technical and coordination variations with George Stone's "Stick Control" and Ted Reed's "Syncopation" are the basis for many of my adaptations using djembé, riq, frame drum, shakers and cajón. I have had some study on hand percussion with Frank Malabe, Trichy Sankaran, Yacub Aday and Glen Velez. Even though I only had a couple of lessons with Glen, his concept for combining a hybrid of ancient world traditions with western concepts has been the springboard for much of my current work.

WPR: You've combined jazz, blues, funk, classical and world music using instruments from a wide variety of diverse cultures such as Europe, Cuba, North Africa, Latin America, Brazil, the Middle East, Southern Italy and South India. What do you think about when you are composing and teaching those instruments so you can put it all together?

Teasley: My process of composing is largely an intuitive one. Through my early experience performing and studying jazz, blues, funk and even European classical music, I have come to know those musics in a practical and academic way. My academic knowledge of classical Indian music and African and Afro-Caribbean music is more peripheral. It would be pretty presumptuous of me to present myself as a master of those musics. My agenda in as much as I ever have one, is to combine my interest in a variety of world music and rhythms with my practical experience in jazz, funk and western classical music. My approach to teaching is also very similar. At Levine School of Music in Washington, DC where I chair the percussion department, we have a great variety of interests among the students. If a student is interested in drum set they will spend some time developing classical snare drum reading and technique. They will also become aware of African inspired rhythms and learn them on a djembe' so they can later interpret them on drum set. We will interpret the rudiments and technique books like Stick Control using hand drum. In addition we will also employ coordination exercises á la Alan Dawson using djembés, shakers, foot tambourine, etc.

WPR: Tell us about your experiences in the recording studio and in doing your videos. Do you do all of the music yourself and layer the tracks?

Teasley: I have developed a rather unusual career as a solo percussionist. My approach is to combine instruments of ancient origin including djembés, frame drums, doumbeks and a variety of tambourines with traditional American and Euorpean instruments such as drum set and orchestral percussion in addition to electronic. When I first began the use of electronics, I was using sequencing in which I would create compositions as well as re-arrangements of jazz standards. Examples of that concept can be found on my CDs "Time Travel," and one selection on "Global Standard Time," as well as my video "The Drum: Ancient Traditions Today." For "Global Groovilization" I would create loops in the studio to serve as a framework. From there I would add hand percussion, drum set and marimba and / or vibraphone. I composed all of the tracks with the exception of "Crystal Silence" by Chick Corea. The new video "Global Fusion Percussion" is a hands on instructional video with booklet covering 1) palm drums, djembé, conga, etc., 2) finger drums; frame drums and doumbek, 3) tambourines, riq and pandiero 4) shaker coordination exercises and 4) drum set applications. At the end of the video there are a variety of performances utilizing all the previous concepts.

WPR: Tell us a bit about your numerous endorsements.

Teasley: I am extremely fortunate to have the support of a wide array of instrument manufacturers. In the same way I combine a variety of instruments, techniques and concepts into my music, I draw on a variety of manufacturers to support my work. I endorse Yamaha Drums and have recently been added as an endorser of Yamaha Band & Orchestra Division, which covers orchestral percussion like marimba, vibraphone, etc. I feel that Yamaha makes the finest drums and concert percussion available. I have a wonderful relationship with Sabian Cymbals and have a cymbal set up now which perfectly compliments my drum set and hand percussion set up. I am using the Ed Thigpen signature crash with flat ride and ride with bell. I am also using the El Sabor crashes, which sound great played with either stick or hand. I use Mountain Rhythym Djembe's and congas. They are beautiful hand made instruments from Canada. They have constructed a custom drum for me, which is a 10" djembé with a sharp edge so as to allow me to incorporate Middle Eastern finger snap technique. I premiered that instrument at last years' PASIC. I use Cooperman frame drums and tambourines. Their drums are true works of art. They have also worked with me to create some custom instruments tailored to my specific needs.

Speaking of drums as art, the work of Steve Wright is a wonderful example. Steve is a wonderful combination of inventor, percussionist and visual artist. His beautiful drums would belong in an art gallery if they didn't sound so great. I use his clay instruments extensively. When possible I fit all my set drums, and hand drums with Remo heads. I especially like the Renaissance and Fiberskin as they give me the warmth of calf or goat with the durability of a synthetic head. For striking implements I endorse Vic Firth products. They have many products of interest to hand drummers. I especially like Blades, Ruté of several sizes and the jazz and rock rakes which are plastic brushes. These companies also financially support my educational efforts and I applaud their commitment to education.

WPR: You've said that drumming is an important tangible element in the spiritual development of people. What is it about the drum that touches this part of us? What is your vision for future generations?

Teasley: The use of drumming to endure a tangible change of human perception has been used for thousands of years. These changes have often been in collaboration with religious or healing ceremonies. These can include Gnawan healing rituals to the dance of the tarantella in South Italy, music of Santeria to Sufi trance music. Who is to say either of those is more healing than the simmering funk of James Brown or even hypnotic beats of London's raves. All sound is vibration and vibration is in all matter. I think that future generations will take the various spiritual / sound connections to a new level. The use of the Internet makes these seemingly disparate traditions easily accessible to anyone who has the inclination.

WPR: Congratulations on your new CD, Global Groovilization and your new video, Global Fusion Percussion (See CD Reviews.) What are your future plans?

Teasley: Thank you very much. It is always important to document one's work and rewarding when others appreciate it. For my future plans I have a new trio project with John Jensen on Trombone, euphonium, didgeridoo and conch shells; Chris Battistone on trumpet, flugelhorn and arranger and I play a variety of world percussion and drum set. I have a new solo presentation called the "Sol Orchestra" in which I loop in real time a variety of percussion, keyboards, mallet instruments and drum set. It is basically a recording session as performance. I stay very busy with the "Word-Beat" project with Charles Williams, my long time friend and collaborator. This project combines the poetry of Langston Hughes and others with my percussive compositions. We also perform a variety of African American spirituals and African folk songs. This project will have a new CD out by early next year. I will also have a new solo CD in collaboration with a horn section out by around the same time. I am also very committed to my teaching at Levine School and the clinics I perform throughout the country. Most importantly I want to continue to grow as a musician and person.

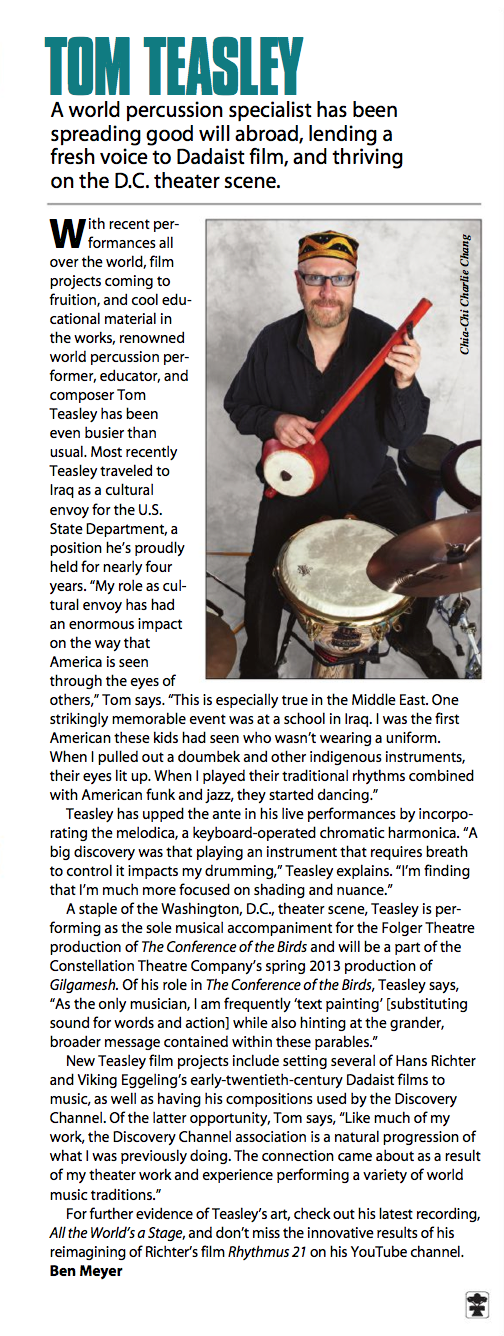

Tom Teasley

A world percussion specialist has been spreading good will abroad, lending a fresh voice to Dadaist film, and thriving on the D.C. theater scene.

With recent performances all over the world, film projects coming to fruition, and cool educational material in the works, renowned world percussion performer, educator, and composer Tom Teasley has been even busier than usual. Most recently Teasley traveled to Iraq as a cultural envoy for the U.S. State Department, a position he’s proudly held for nearly four years. “My role as cultural envoy has had an enormous impact on the way that America is seen through the eyes of others,” Tom says. “This is especially true in the Middle East. One strikingly memorable event was at a school in Iraq. I was the first American these kids had seen who wasn’t wearing a uniform. When I pulled out a doumbek and other indigenous instruments, their eyes lit up. When I played their traditional rhythms combined with American funk and jazz, they started dancing.”

Teasley has upped the ante in his live performances by incorporating the melodica, a keyboard-operated chromatic harmonica. “A big discovery was that playing an instrument that requires breath to control it impacts my drumming,” Teasley explains. “I’m finding that I’m much more focused on shading and nuance.”

A staple of the Washington, D.C., theater scene, Teasley is performing as the sole musical accompaniment for the Folger Theatre production of The Conference of the Birds and will be a part of the Constellation Theatre Company’s spring 2013 production of Gilgamesh. Of his role in The Conference of the Birds, Teasley says, “As the only musician, I am frequently ‘text painting’ [substituting sound for words and action] while also hinting at the grander, broader message contained within these parables.”

New Teasley film projects include setting several of Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling’s early-twentieth-century Dadaist films to music, as well as having his compositions used by the Discovery Channel. Of the latter opportunity, Tom says, “Like much of my work, the Discovery Channel association is a natural progression of what I was previously doing. The connection came about as a result of my theater work and experience performing a variety of world music traditions.”

For further evidence of Teasley’s art, check out his latest recording, All the World’s a Stage, and don’t miss the innovative results of his reimagining of Richter’s film Rhythmus 21 on his YouTube channel.

Ben Meyer